How the MEMO Method Ruined My Life and Turned Me into a Writer and Book Lover

I was supposed to be entering the Baseball Hall of Fame this year, dammit.

I had a normal childhood, at first: My brother, Yan,1 and I would cover the living room with plastic army men and engage in complex war games that always ended with Godzilla decimating entire battlefields2. I played a series of complex games with the other urchins of my neighborhood, each with fluid rules, some of which have not, technically, ended yet. And I dreamed of being a professional baseball player. Or a magician, if that didn’t work out; it seemed likely that the skills were pretty transferable.

A few years later, everything had changed. Suddenly, I was a pudgy kid in enormous glasses who had the dexterity of a rock. Was it hormones? Dark magicks? The sudden, late-night realization of my mortality? Well, yes to that last one, but also, no, it was something else entirely: I was forced to read a book.

Minimum Effort

During that brief, happy period of my life when I was a skinny idiot who won every footrace he was challenged to on my block (and that’s a lot of footraces3), things came relatively easy to me. I independently developed the philosophy known as MEMO: Minimum Effort, Maximum Output. I approached every assignment and problem with the absolute minimum effort required to accomplish it. To this day I do not understand why people do more than the absolute minimum in any situation.

So when my teacher forced the entire class to walk six blocks to the local library and select a book we would then have to read and write a report about, I immediately knew what I would choose: A book of magic tricks. My reasoning was unassailable:

- Probably very few words.

- Probably a lot of pictures.

- It would simultaneously be training for my backup career4.

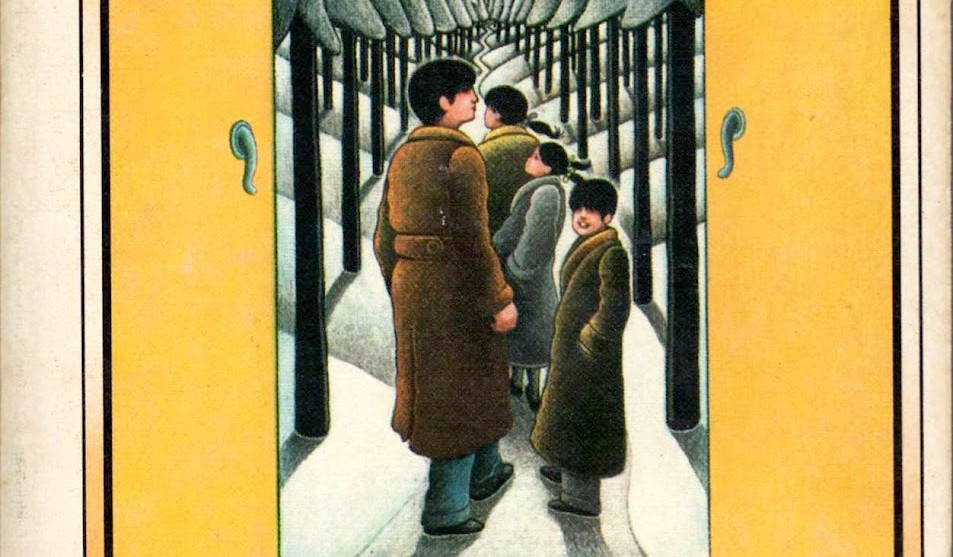

And then the plan went to hell and my life changed, because several months earlier I had watched The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe on television.

Maybe I should back up.

The Memory Hole

I am an old, old man5 and the world has changed a lot since my carefree youth. When I was a kid, television was terrible, but to compensate for this terribleness the universe had made it also very transient. There would be a truly terrible program—maybe an episode of The Love Boat, literally any episode—and it would make the world a worse, dumber place while it was airing6. But then it would be over, and it would be gone, because back then there was no recording. No VCRs, no DVRs, no cloud storage, no Internet. You watched a show, it ended, and that was it. Some shows were re-broadcast, but not everything, and not reliably.

There was an animated adaptation of The Lion, the Witch, and The Wardrobe on TV and I was transfixed. And then it was over and I returned to my regular schedule of eating crayons to see if my poop turned colors7. And then I was herded into a library to select a book to read, and there was The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe. Being something of an idiot, it had never occurred to me that TV shows might be based on something like a book. I was stunned, and for the first time in my young life, I wanted to read a book.

I took all seven Narnia books out, read them all, and then read them again. I repeated this process over and over again, staying up late under the covers to read by flashlight, my hair turning white, my eyes failing, my desire to learn how to throw a curveball fading. Instead of learning how to find quarters behind people’s ears—a skill that would have set me up for life—I started writing my own stories. A skill which has not set me up for life8.

Now here I am, a Gollum-like creature who hisses at the sun and spends his days in the glow of a screen, writing stories and novels and self-serving essays that make me—and likely no one else—giggle in a very unattractive manner. And it’s all because I was forced to read a book. I may sue.