How to Write a Story

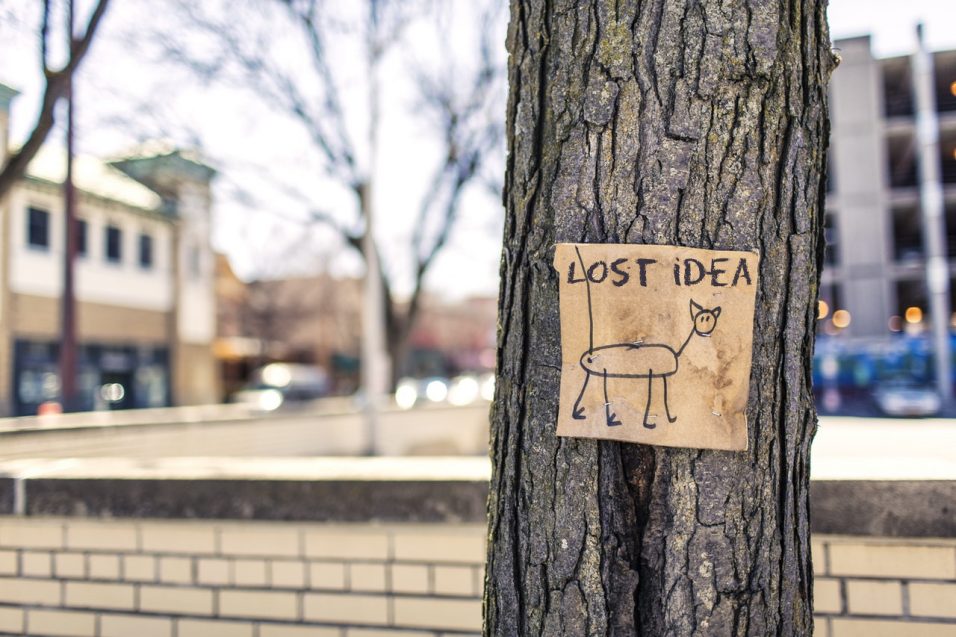

One of the most basic and common questions a writer gets is ?how do you come up with ideas’ or ?how do you write a story,’ both of which are almost koan-like in their complex simplicity. While some folks see margin in making the writing process extremely complicated and filled with jargon and mystery, it really isn’t that hard. In fact, I’m going to show you how to write a story right now. If you’ve never written a story ever, this is for you.

One disclaimer: The story you write may not be a good story. And finishing it is up to you. But using this incredible secret, anyone—literally anyone—can write a story. Here goes.

Step 1: Imagine a Scenario

Start with any sort of scenario. It could be a Half-Dog, Half-Man Warrior in the depths of space trapped on a spaceship rapidly leaking oxygen, or it could be an old man weeding his garden on the last morning of his life. Or anything, really. Just imagine a scene. Crib something from your own life if you can’t drum up something purely imaginary.

Step 2: Imagine Something Unexpected

Next, ask yourself what the people in your scenario expect to happen. The Half-Dog Warrior might expect to die. The old man might expect to have breakfast in a few minutes, once he’s done with his gardening. Then, make something else happen. Something unexpected. The Half-Dog Warrior suddenly picks up a distress call. The old man sees Death, a corporeal hooded figure, lounging in a lawn chair across the street, waving.

Now, imagine how the character reacts to something unexpected. There’s your story.

Step 3: End the Damn Thing

Ending it can be hard, but only if you insist on a clever, or mind-blowing ending. If you decide you just need to end it, it’s easy. Do that. Clever or mind-blowing tends to happen when you’re not looking, so by pursuing endings of any kind you’ll wind up with finished stories, some portion of which will be brilliant in their endings.

The Half-Dog Warrior breaths his last bit of air as the young puppy he rescued speeds off in the ersatz escape pod he fashioned. The old man invites Death in for tea, and Death, startled, decides to spare him. Whatever. The Warrior flies into a star just to see what it’s like, or crosses the Event Horizon of a Black Hole to experience eternity in a moment. The Old Man sets his house on fire in his last excruciating moments, out of simple bitter rage. Whatever.

See? Stories are easy. The hard part is actually writing them down.